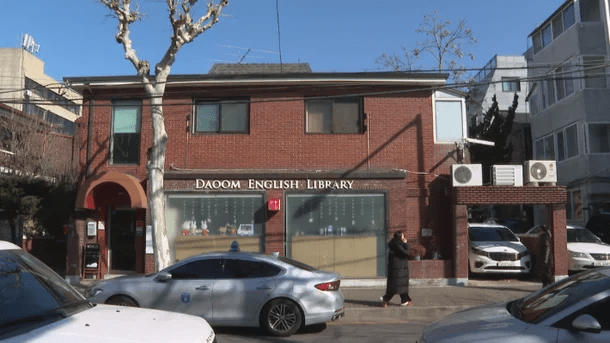

Juyeon is a Grade 11 student living in Daechi-dong, an area widely known for its concentration of private academies. She has lived her entire life in Korea and has attended only Korean public schools, while spending most of her evenings and weekends at hagwons preparing for major exams. As a humanities track student, she feels strong pressure to perform well academically, since university name plays a major role in future opportunities. Her daily routine reflects the reality of many Korean students growing up in an exam focused education system shaped by competition, financial gaps, and social expectations. Through her experience, Juyeon offers insight into student life inside one of Korea’s most academically intense environments.

What does a typical weekday look like for you as a student in Daechi-dong?

Juyeon: On weekdays, I wake up early for school and spend the whole day in classes. As soon as school ends, I head straight to academies. I attend different hagwons for Korean, English, and social studies, and I usually get home close to midnight. Even after that, I feel pressure to review what I studied or plan the next day. There is barely any time to rest, and studying shapes almost everything in my daily life.

How does studying in Daechi-dong affect the way you see school and learning?

Juyeon: Being in Daechi-dong makes learning feel competitive all the time. You are surrounded by students who study longer hours or attend more academies, so it is hard not to compare yourself. Sometimes learning feels less about interest and more about surviving the system. I still enjoy certain subjects, but the focus on scores and rankings makes it difficult to fully enjoy learning.

What do you think about the exam and academy centered study culture in Korea?

Juyeon: I think this culture pushes students to work extremely hard, but it also creates constant pressure. Studying becomes something you have to do rather than something you want to do. While the system can produce strong academic results, it does not leave much space for students to rest, explore interests, or think about who they are outside of grades. I believe education should support growth in more balanced ways, not just prepare students for exams.

![책꽂이] 학벌주의가 낳은 '기이한 아수라장' 대치동의 민낯 | 서울경제](https://newsimg.sedaily.com/2021/11/25/22U5L7XIA0_7.jpg)

Juyeon’s story reflects the reality of student life in Daechi-dong, where long study hours, competition, and expectations shape everyday routines. Her experience shows how Korean students balance public school, private academies, and social pressure in an environment where academic performance carries heavy weight. At the same time, her reflections reveal the emotional strain of growing up in an exam centered system. Through her perspective, we gain a clearer understanding of how education and culture shape student life in Korea, and how young people continue to search for direction while studying under constant pressure.