In recent years, Korean content has traveled far beyond its borders, capturing the attention of global audiences with its music, dramas, and increasingly, its broadcast formats. But behind the scenes of this cultural export boom lies a lesser-known figure: the broadcast format producer.

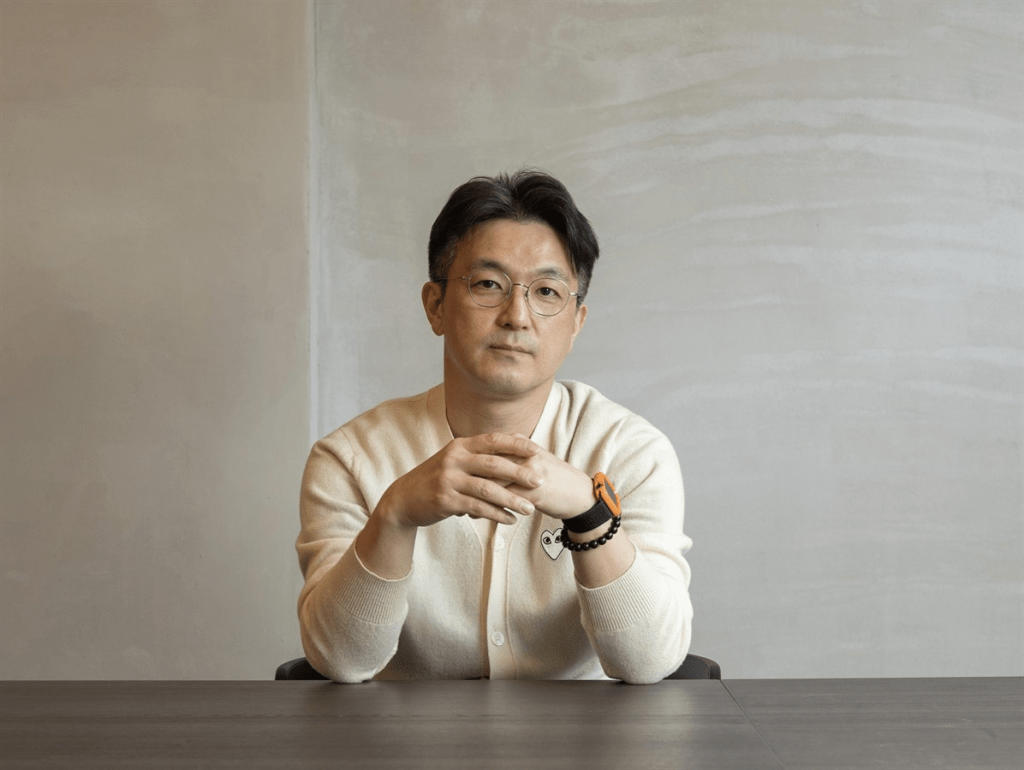

This is a photo of Wonwoo Park, the CEO of diTurn.

Wonwoo Park is the Founder, Show Director & CEO of Korean broadcast format company diTurn. Park is internationally recognized as the original creator and Korean producer behind global sensations like The Masked Singer and Lotto Singer. In Korea, he has also developed and produced a number of successful shows, including 300: United Voices, My Ranking, Dancing in the Box, and My Boyfriend is Better. Following the worldwide success of The Masked Singer, his company, diTurn, secured a first-look deal with FOX TV and is now collaborating with major global studios such as Sony Pictures and Banijay. In this interview, we explore with Park, how Korean cultural identity is packaged, adapted, and sometimes challenged when entering foreign markets, and what this process reveals about the contrasts between Korea and the rest of the world.

What exactly does a broadcast format producer do? What kind of work are you currently engaged in?

Wonwoo: The role involves identifying and analyzing global media platforms and broadcaster needs, often detecting trends and assessing market flows. I work closely with domestic broadcasters and production companies to create customized formats. I also collaborate with overseas partners to co-develop formats tailored to international audiences and ensure these projects are successfully launched abroad. Once a format gains traction, I continue managing and evolving it, generating new ideas for future formats and adaptations.

How do you see Korea’s culture and content industry being received overseas, especially when working as a format producer?

Wonwoo: Korea’s cultural exports, once limited to stereotypical notions like “politeness” or “group harmony,” have now expanded into mainstream media through K-pop, K-drama, K-animation, and K-format. Major international buyers are increasingly interested in Korean creativity and originality. I can say how Korean-made formats are gaining attention for their innovative and structured storytelling. As evidence, exclusive format licensing deals with NBCU and FOX TV signal Korea’s elevated status in the global media market. I believe that the future holds even greater opportunities for Korean content to gain love from international audiences.

Have you ever experienced cultural differences or challenges while working with international partners?

Wonwoo: Absolutely. Cultural and workflow differences often present challenges. For example, international partners tend to plan with detailed schedules and emphasize business results, whereas Korean workflows are more flexible, relying heavily on trust and relationship-based collaboration. These differences sometimes caused confusion and miscommunication in the early stages. However, through hands-on experience and frequent local coordination, I learned how to bridge those cultural gaps. I’ll emphasize that understanding each other’s processes is crucial to building transparent and productive partnerships.

What do you think are the key selling points or unique traits of K-formats for global buyers?

Wonwoo: The distinctiveness of Korean formats lies in their balance of clear structure and emotional depth. These formats often reflect Korea’s cultural values, such as sincerity and resilience, which resonate with global audiences. Even when adapting similar themes, such as survival shows or romance, the Korean version tends to add a fresh perspective, often grounded in realism and emotional storytelling. For example, themes of regret, social class conflict, or generational tensions often appear in Korean formats, giving them universal relevance. This cultural richness, paired with competitive production quality, makes K-formats a strong contender in the global market.

What becomes clear through this conversation is that Korean culture is not simply being exported—it is being negotiated. The broadcast format producer navigates differences in work style, creative values, and narrative expectations to ensure that Korean content can land meaningfully in other cultural contexts. At times, this means adapting or even compromising parts of Korea’s unique storytelling DNA. Yet, in that very process of cultural exchange, Korea also gains insight into how it is perceived globally, and where its values align—or clash—with others. These are not just stories of entertainment—they are reflections of identity, power, and cultural dialogue. And perhaps, in seeing which parts of Korean culture are embraced or misunderstood abroad, we also see the shifting landscape of what Korea represents to the world.

Read the blog about Boom (Minho Lee), another creative worker as an entertainer in K-media industry!