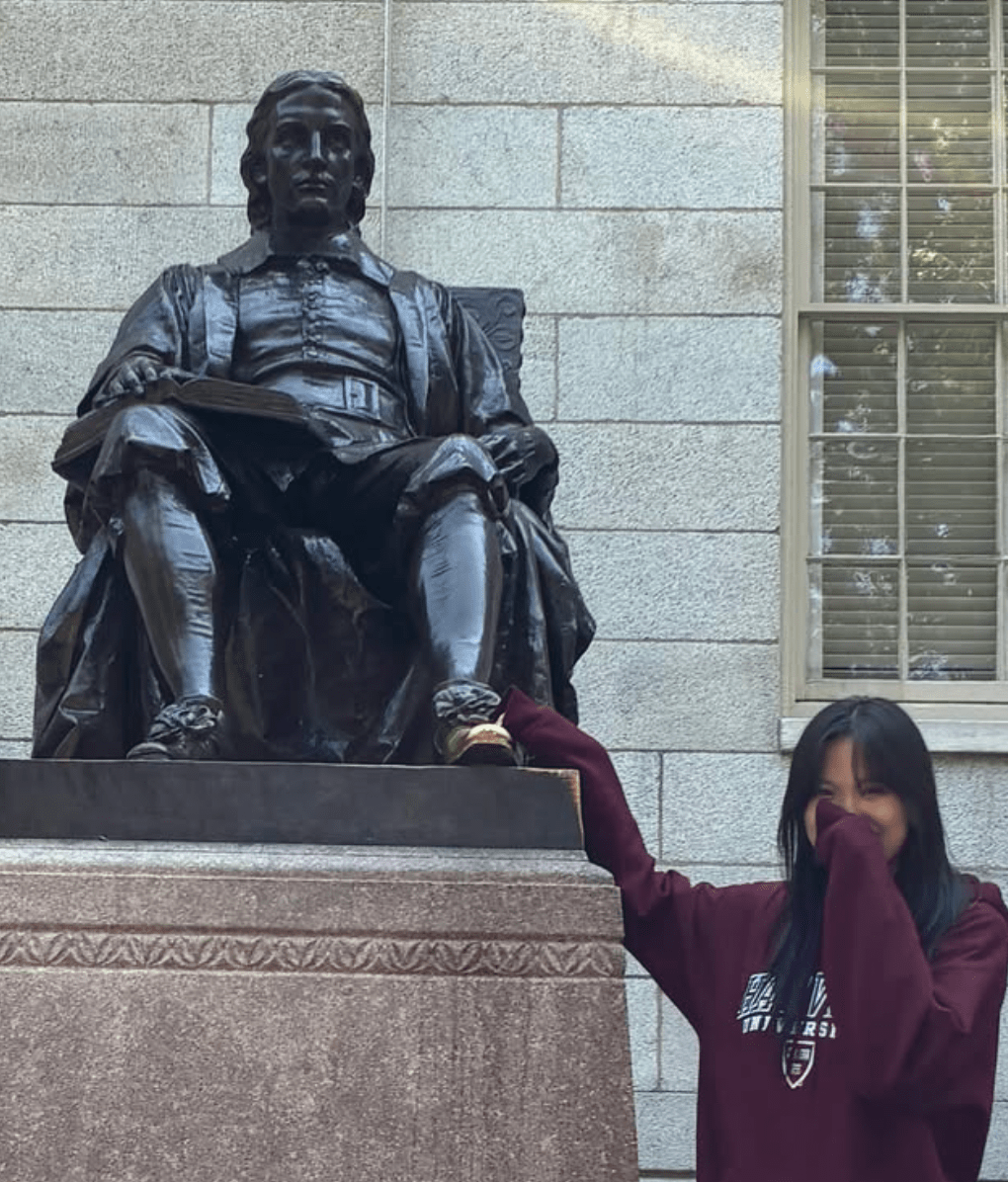

Jiwoo Choi is my sister and a rising freshman who has recently been accepted into Saint Paul Preparatory School in the Seocho district. She has attended more than four different international schools in Seoul, all of which have either an English or American curriculum, despite never having lived abroad. Her perspective differs significantly from that of the majority of international students, as her only source of connection to her home language or culture comes from within her family, while she is neither a second-generation immigrant nor does she have permanent residency in any foreign country. Jiwoo provides insight into the challenges of having a strict social and cultural division, and is concerned with how she doesn’t have a single standard of living. This is amplified since her career, following her studies abroad, will most likely require her to reside overseas, and she is unsure about selecting a country when she has only ever experienced a mixed environment.

Sieun: Please introduce your personal and academic background.

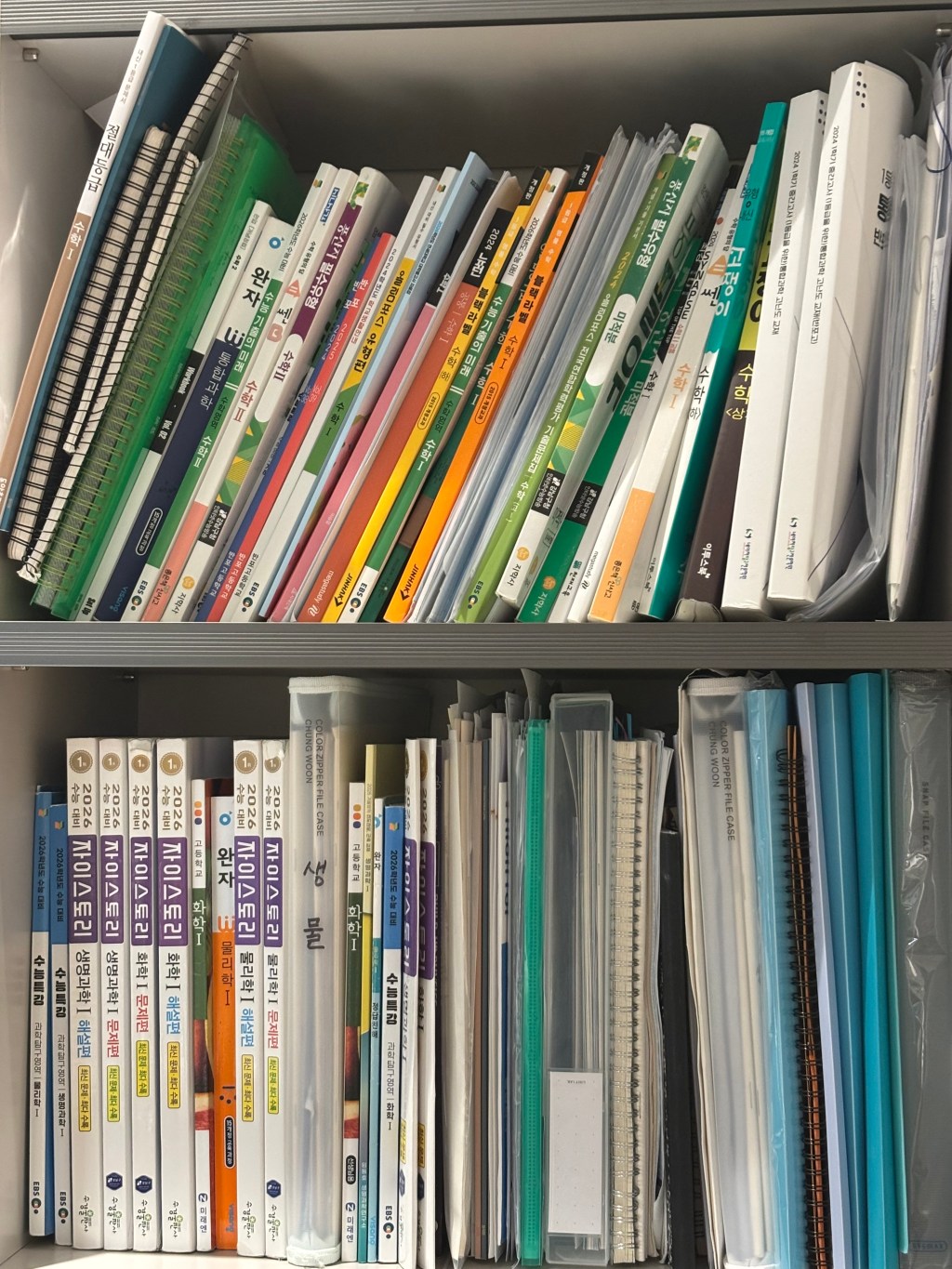

Jiwoo: I’m Sieun’s little sister, Jiwoo. Unlike Sieun, I’ve never attended Korean public school, and every one of my friends and acquaintances is an international school affiliate. I’ve studied according to American textbooks most of my life, and speak Korean only at home. I have moved frequently within Seoul, changing schools, and I’ve also traveled abroad a lot.

Sieun: How would you describe your school and social life compared to your life at home?

Jiwoo: I think the simplest yet greatest difference is language. A social studies teacher once showed our class a TED talk about how language shapes cognition, not only in terms of grammar, range of expressions, and meanings, but also in the way people carry themselves. That was the most relatable thing I’ve ever heard. In school, where I speak English and also mostly follow North American social cues because there are foreign teachers and students, I act more sociable in some sense, but on the other hand, try to stay out of others’ and my boundaries more, like being extremely talkative and bubbly but at the same time only touching on surface-level conversational subjects.

At home, not only with my direct family, but also during holidays when we travel to our grandparents’ house to meet relatives and random visitors, I sometimes feel a sense of discomfort around people, especially the elders, who ask more about my business. But I also think that I’m being cared for more.

Sieun: Were there any difficulties from this divide?

Jiwoo: I’m a student, so most of the time I’m occupied with homework, studies, clubs, and other school-related activities, even at home. Honestly, apart from that, I speak Korean at home, and just in the streets, and I notice little cultural differences in, like, the way people greet each other, I don’t really experience a totally “Korean” lifestyle. But if you think about it, I also can’t say that I identify with the American nationality. I’ve also been in English schools, and the range of an international school that I experienced is huge. So, the conversations I have and the media I consume just have a vaguely North American hint in a spatially Korean context. I know that not all International students are this unsure or even see this as a problem. Still, I sometimes feel anxious that I don’t have the strongest national pride or connection to Korea, apart from its geographical location, and neither to America, apart from what I have been exposed to through the international school system. It can feel like I’m not entitled to either, and sometimes like I don’t belong anywhere.

Sieun: In the future, how do you think you can manage this discomfort, and decide where to either spatially or emotionally settle?

Jiwoo: All the education I’ve ever had is in English, so I’m set on going abroad for my bachelor’s degree. I’m actually kind of excited, because at least then, I’ll have a few years to experience one nation fully. I’ll decide where to reside for the rest of my life after experimenting. I also always felt like I would need at least a short-term work experience in South Korea, because my family is here, and I’ll honestly just have to give everything a try. I would have to consider realistic factors, such as whether I can secure a visa elsewhere and if I’m ready to leave one of the safest countries, both literally and emotionally, for me. Because there is comfort in homogeneity, and I’m unsure whether studying abroad will make me miss it or disregard it.

Jiwoo’s interview reveals the effects of the lack of a single national identity or pride on a developing teenager. She shares the common experience of an international student or a second-generation immigrant, which is having to switch languages completely from their school and social life to their familial interactions. Apart from the way this language barrier sometimes creates cultural barriers, since language dictates thinking, as she mentioned, her anxiousness toward her national identity comes from having a school-centered life, almost without any Korean social influence, except that from her parents. Her willingness to take risks by experimenting with life in different countries to discover what shapes her mind and identity to their fullest potential is admirable. This kind of openness towards selecting one’s own culture or cultures, and ultimately their lifestyle, is increasingly needed as we move forward in globalization.